Fieldcraft

Getting in and out safely

Hi, I am a landscape and nature photographer based in Melbourne, Australia and enjoy using my camera to explore our remaining wild places and better connect with nature.

In my last newsletter, I recalled a very productive session photographing trees in fog, along with a discussion on whether or not a consistent style is important. This newsletter is about a photography session with the opposite level of photographic success (all photos are from different trips in the same region), and the importance of fieldcraft in wilderness photography. Enjoy.

Finally, I stood in the misty rain looking across the mountain stream cascading down the side of the Baw Baw plateau in Victoria’s Central Highlands. I paused to catch my breath and take in my surroundings.

Behind me was a magnificent Mountain Ash forest with trees reaching 70 or 80 metres into the mist, crowned by a mass of branches sprouting out in all directions, draped with long strips of bark. The understory was a thick tangle of scrub I was pleased to be out of.

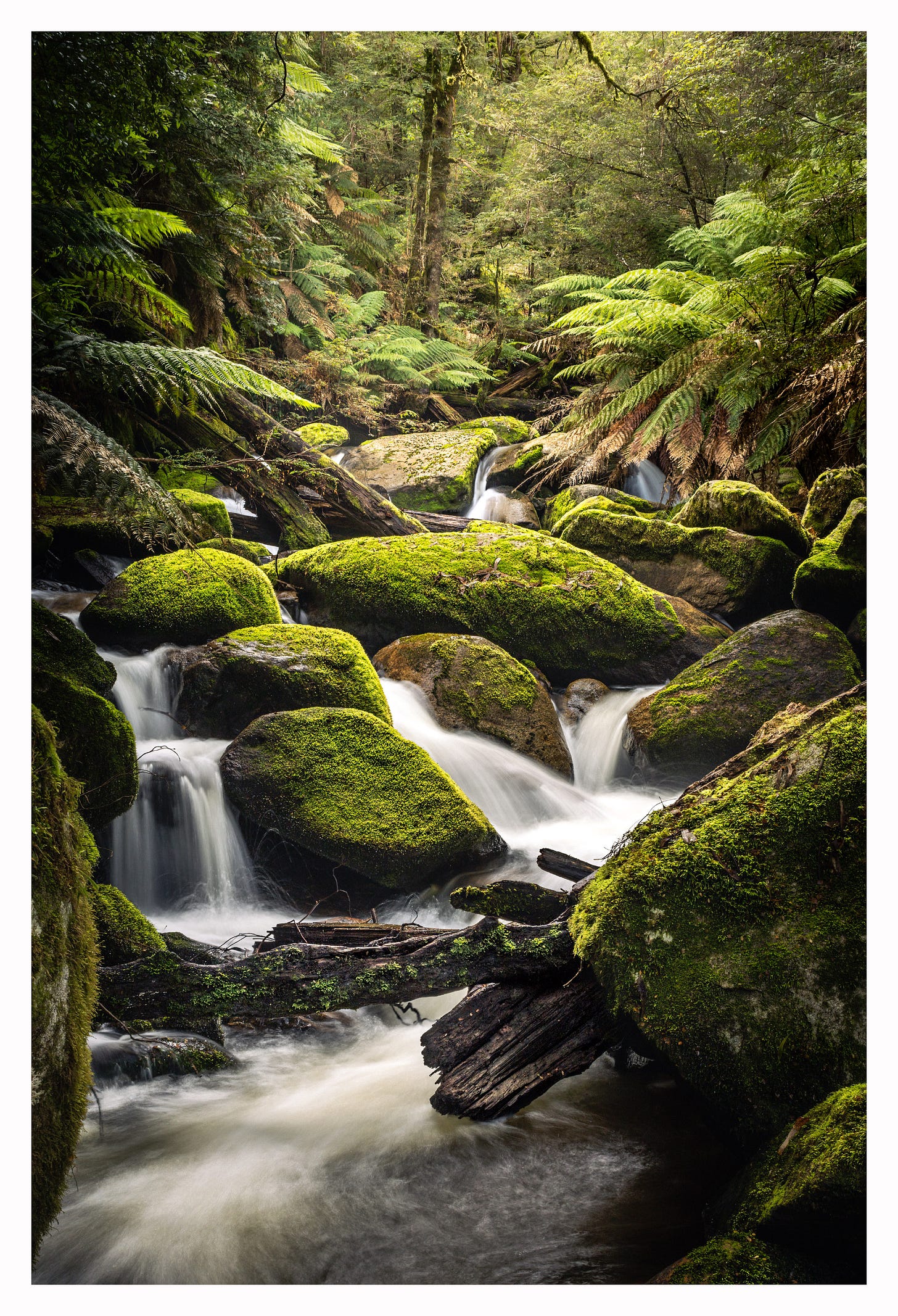

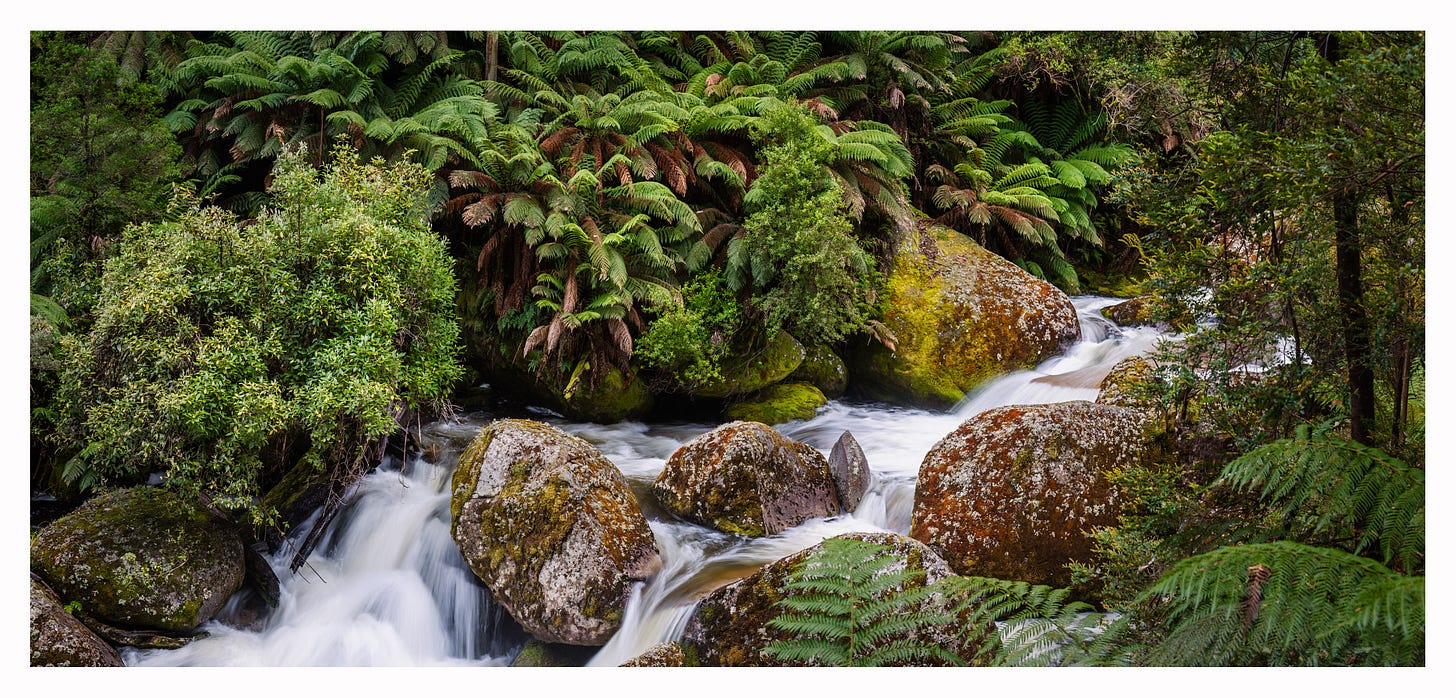

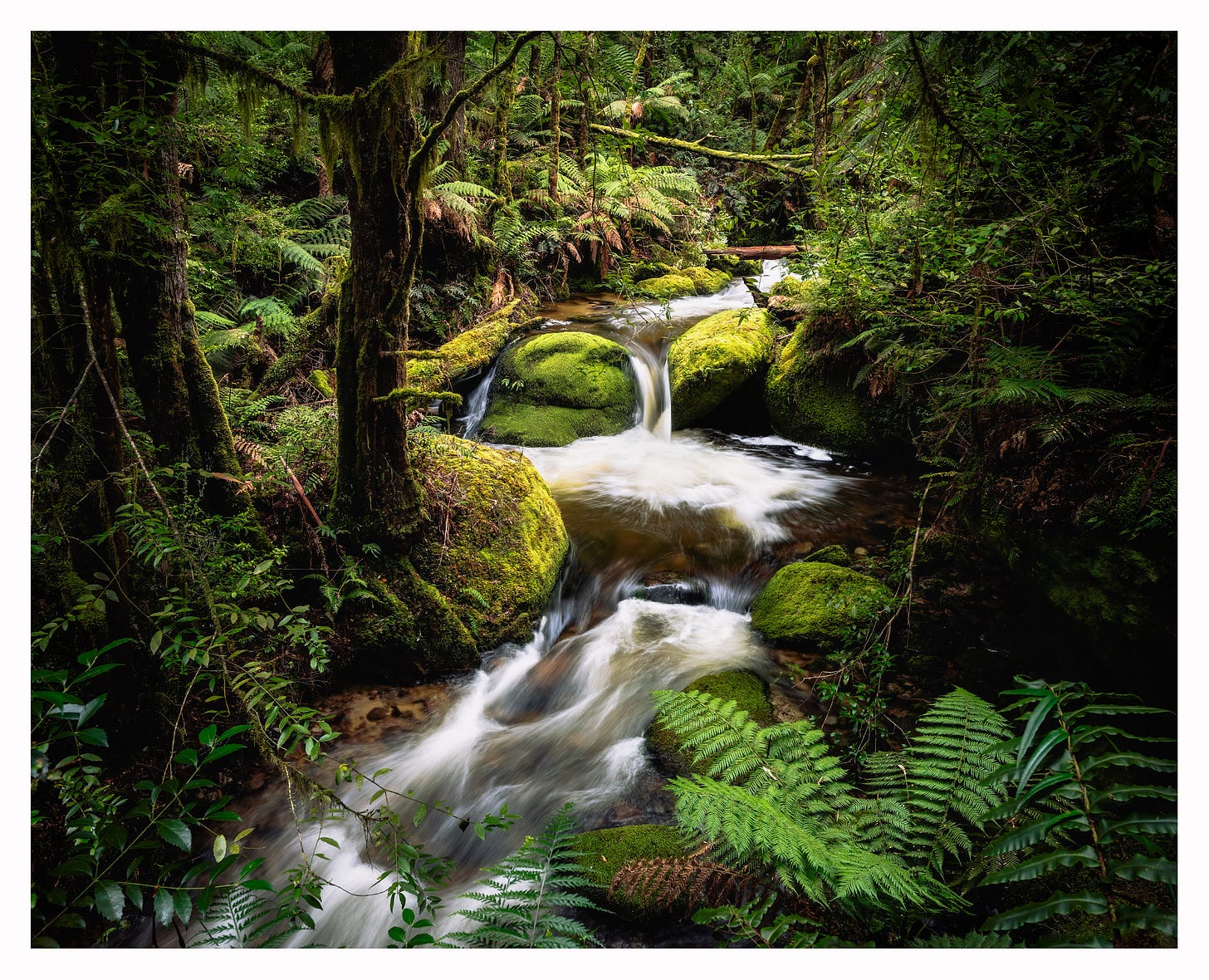

In front of me was temperate rainforest, full of the dark greens of Myrtle Beech and Sassafras, surviving on the wet, steep slopes either side of the stream. The understory was more open, with extensive tree ferns, boulders and fallen timber clinging to the river edge.

With the soft rain, the smell of the rich, loamy soil and the constant roar of water, I felt completely immersed in the landscape.

I was standing next to a Mountain Ash that had fallen over some distance up the slope, creating a near impenetrable barrier that extended 80 metres down the slope and across the river. The vast size of this fallen giant was quite intimidating.

Where the fallen tree had crossed the river, other debris had got caught forming a small pool the full width of the stream, only 3-4 metres wide at this point. It looked deceptively calm although the river was flowing strongly from the consistent rain and snow melt over the past few weeks.

Both above and below the pool, the stream was a continuous cascade of multiple channels of pure mountain water flowing between large moss-covered boulders. It would require great care to negotiate the steep banks, slippery rocks and fallen trees to get down to water level where the best photographs awaited, like the one below.

I had carefully planned the journey to this location – just a spot on the map that looked prospective. Using topographical maps and Google Earth, I had mapped a 2.2 kilometre walk up the mountain side using a disused management track to gain height from the main road, and then a 1 kilometre off-track traverse across the mountain side to the stream.

Although the location and conditions were everything I could have hoped for, there was a problem - my fieldcraft had let me down.

Fieldcraft is one of the distinct skill sets I am constantly refining to improve my landscape photography practice. I define it as the ability, as I go out and explore remote and less seen locations, to get in and out of an area safely and in a way that supports intentional, immersive photography.

The other skill sets I work on are:

Camera craft - the ability to capture data in a way that will allow me to make effective images of what I saw, while not destroying cameras.

Processing - making sense of the RAW files to communicate what I want to say.

Editing - as in curation and sequencing of images.

I think this is a useful structure to think about developing the required skills as a photographer, although the specific skills may change for different genres of photography1.

I had significantly under-estimated the difficulty of getting into this location. The steep walk up the disused management track, although full of vegetation, was not a problem. However, the traverse was a horror of thick scrub, wet and near impossible to push through. Any progress required climbing and crawling through the horizontal scrub, often not being able to see my feet and requiring balancing on slippery fallen timber well above the ground (the image below is not of the difficult thick scrub, these tree ferns offer relatively easy, open bush bashing). At one point, it had taken 45 minutes to cover less than 300m.

All up I had taken 4 hours to walk just over 3 km (as the crow flies) to the stream’s edge and, despite starting at sunrise, it was now 11.30 am.

There was a difficult decision to be made – do I proceed downstream as planned, exploring the stream and bush bashing through to another management track, or do I turn around and back track through all that terrible scrub?

I had arrived at the river soaked through and short of time. Although I had additional dry layers, keeping warm would be a challenge, and not conducive to slowing down and absorbing the landscape, testing and feeling out potential compositions that would do the location justice. I also didn’t know how long the walk downstream and bush bash to the road would take. Given my current pace, daylight might become an issue.

In addition, I felt the risks were rapidly increasing. If I fell or had some kind of accident that prevented me from moving, I probably didn’t have enough warm clothes to manage a long wait for help once I activated my Personal Location Beacon (being well outside mobile phone reception).

I found a small gap of perhaps 30 cm between the soil and the massive fallen tree beside me that allowed me to wriggle through on my stomach, pushing my backpack ahead of me. On the other side I did a quick scope of river and decided that I was too wet and any exploration would take too much time.

I knew the decision I had to make. No longer wanting to search for compositions, I took three (bad) photos, just on principle, and then turned around to face the next two hours of thick bush bashing back the way I had come to the management track.

I had plenty of time to reflect as slogged back through the scrub and then down to car – a 2.5 hour drive each way and over 6 hours of tough walking with no photos. Although disappointing, this is the nature of landscape photography. While I had made some mistakes and made some assumptions that proved incorrect, I also had a great adventure and got to spend time deeply immersed in bush that few people get to.

There were also things that went well. Although the terrain was very difficult, I did not get lost (always a good outcome!) and the traverse was well within my physical and mental capabilities. Near impenetrable bush can be very tough on the body and mind. Perhaps most importantly, I made good decisions to assess options and manage risk.

I remember hearing someone say that the key to photography was proximity and access. For a landscape photographer, this often means getting out in challenging terrain and conditions. While I would not get out as often as I do or to the places I explore without the motivation of photographing these landscapes, it is the deep love and respect for Nature, especially the forest landscapes, that drives me.

Already I am planning another trip to this area – I can get a bit obsessed about exploring a location – something less ambitious that will get me to the river in less time and better shape to allow me to slow down, absorb the location and find the compositions.

For example, a portrait photographer will not need strong wilderness fieldcraft but will need expertise in directing and managing people. Their camera craft may be less about managing high dynamic range, raindrops on the lens or condensation and more about backdrops and studio lights. Processing may be more retouching than focus stacking.

These shots are fantastic! I know the feeling of working your butt off and not getting any photos. Makes you feel alive though :)

I'm just now getting caught up to the point of reading this, and I'm so glad I did! This reminds me of my trip to the Canyon of Five Falls back in the early spring. Fieldcraft has been a passion for me long before I ever picked up a camera. I really like how you categorize it as a distinct but important skill set related to other photography skills.